In 1972, Vincent Darrell Groves was the definition of a golden boy. Standing six-foot-five on the polished hardwood of Wheat Ridge High School, he dominated the court, the star player of a championship-bound basketball team. He was popular, charismatic, and the only Black student in his graduating class. With an easy smile and natural magnetism, his future seemed to stretch endlessly ahead of him, wide open and full of promise.

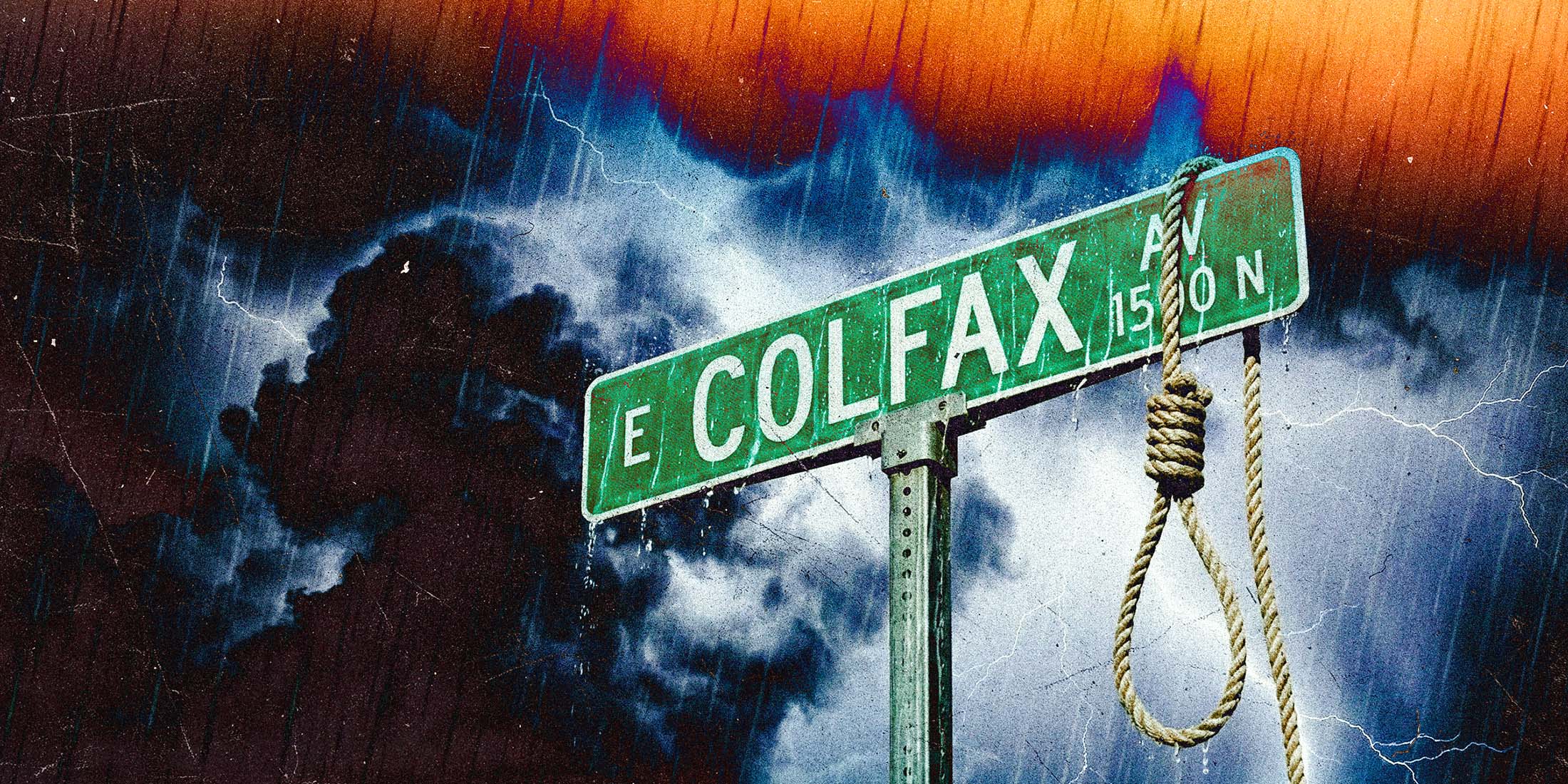

He did not go to the NBA. After dropping out of college in Iowa, Groves returned to Denver and drifted toward East Colfax.

By the late 1970s, the letterman jacket was gone, replaced by the gritty uniform of the street. Groves worked odd jobs, first as an electrician, later as a janitor, but his real life unfolded after dark. He became a fixture along East Colfax, dealing cocaine to pimps and sex workers who populated the neon-soaked strip. To the women he met, he was a charming, hulking presence, someone who could talk his way into their cars and lives before literally squeezing the life out of them.

Groves died in prison in 1996 at age 42, his liver failing before the justice system could fully catch up but thanks to extraordinary forensic breakthroughs, investigators now know his reign of terror was far bloodier than history once recorded.

His method was brutal and intimate: strangulation. He did not use guns. He used his hands, or sometimes a cord fitted with a pre-tied slipknot, a chilling detail that made clear his crimes were never spontaneous acts of passion, but deliberate, premeditated violence.

His first conviction for murder came in 1982 and ended in a twist that still defies logic. The victim was Tammy Sue Woodrum, a 17-year-old hitchhiker Groves picked up and drove into the mountains. After killing her, he did not flee. Instead, he returned home to his wife, Jeanette Hill, and told her a story of panic and tragedy.

Groves claimed Woodrum had died of an accidental overdose in his car. Hill urged him to do the right thing and go to the police. Groves walked into the station and surrendered, repeating the overdose story.

The coroner’s report told the truth. Woodrum had been raped and strangled.

Groves was convicted of second-degree murder. In a decision that now reads as catastrophic, he was released on mandatory parole in 1987 after serving just five years of a 12-year sentence.

Once free, Groves wasted no time. He moved in with Juanita “Becky” Lovato, a 19-year-old woman who trusted him enough to share her home. In April 1988, her naked body was found dumped in a rural field east of Denver. The man she lived with had killed her, strangling her just months after regaining his freedom.

Around the same time, Groves crossed paths with Diane Montoya Mancera, 25. Her body was later discovered in neighboring Adams County. These two murders finally locked him away for good. Evidence showed Groves was the last person seen with Lovato, and a friend of Mancera testified to seeing her get into his car shortly before she disappeared. In 1990, Groves was sentenced to life in prison for Lovato’s murder, along with an additional 20 years for Mancera’s.

As Groves sat in his cell, silent and unrepentant, the ghosts of his other victims waited in evidence lockers. When he was dying in 1996, detectives visited him one last time. They asked for names, for confessions, for anything that might bring peace to the families left behind. Groves refused. He chose to take his secrets to the grave, attempting to deny his victims even that final dignity.

Science, however, would not allow his crimes to remain hidden.

In 2012, DNA evidence linked Groves to three women killed in 1979. Emma Jenefor, 25, was found dead in a Cherry Creek bathtub, staged to look like a suicide. Joyce Ramey, 23, was discovered in an industrial park. Peggy Cuff, 20, was found in an alley.

As recently as December 2025, investigators were able to connect Groves to a 38-year-old cold case. For decades, the family of Rhonda Marie Fisher waited for answers. Fisher was 30 years old, a mother, a daughter, and a friend. On the night of April 1, 1987, during the brief and deadly window when Groves was out on parole, Rhonda vanished while walking in Denver.

Her body was found the next day, discarded down an embankment off South Perry Park Road in Douglas County. She had been sexually assaulted and strangled.

At the scene, a coroner made a small but critical decision. Paper bags were placed over Fisher’s hands to preserve any trace evidence she might have collected while fighting for her life. Those bags were sealed away in cold storage, where they sat for nearly four decades.

In late 2025, investigators reexamined the evidence. They discovered that microscopic DNA had transferred from Fisher’s hands onto the inside of the paper bags during storage. That trace DNA produced a direct match to Vincent Groves.

“Obtaining a DNA profile from paper bags nearly 40 years old is exceptionally rare,” Douglas County Sheriff Darren Weekly said in a December announcement.

Today, authorities believe Vincent Groves may have killed as many as 20 women. He targeted those he believed society would not protect, sex workers, hitchhikers, women living on the margins. He counted on indifference.

He was wrong. Science kept the receipts. And one by one, the women Vincent Groves tried to erase are finally being heard.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.