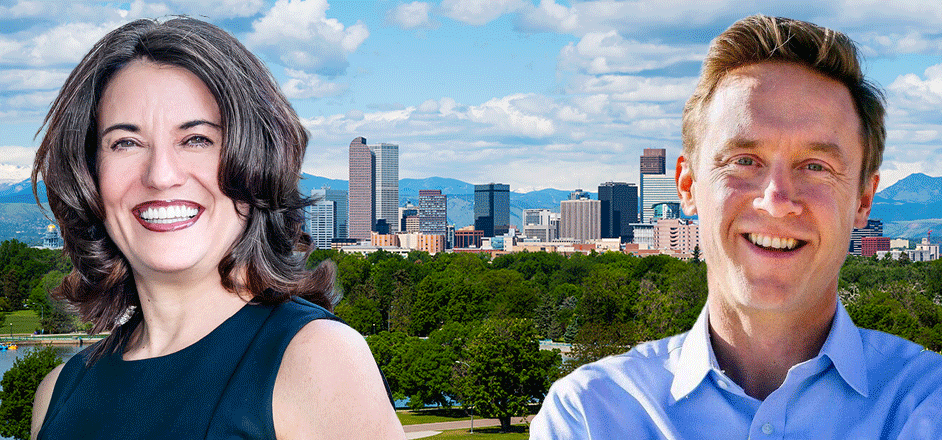

After speaking to both Denver mayoral candidates Mike Johnston (D) and Kelly Brough (D), one thing becomes clear: for the subsection of its citizens who may be homeless or otherwise downtrodden, the cavalry is on its way.

On April 4th, registered voters from every demographic of the state capital will come together and elect the next mayor of the major metropolis. And at the end of the tally, I can comfortably say that whether it is Johnston or Brough that is pronounced the victor, the city will be in capable hands.

When compiling the questions for these interviews, I wanted to ask about the topics that are consistently at the top of public concern polls, along with other subjects that directly impact Denver’s citizens. These include homelessness (along with some of the systemic issues surrounding it like addiction and mental health issues), public safety nets like affordable housing, and Denver raising the minimum wage to a living one.

But before we tackle those pressing matters, I think it’s important that we look at what qualifications each of these candidates possesses, and what makes both of them incredibly qualified for the job.

Brough has worked for all 13 members of the Denver city council, along with John Hickenlooper in the legislative branch as a legislative analyst. She also served as Chief of Staff for both the city under Hickenlooper and during the Democratic National Convention. She was also the first woman elected president of the Denver metro Chamber of Commerce. Finally, she balanced the city budget during the Great Recession in 2009.

Johnston was formerly a state senator for the 33rd district in Colorado from 2009 to 2017. Before that, he was the education advisor for former President Obama during his 2008 campaign run. He also ran Covid check—an organization with 1,500 employees and 50 test sites—that gave vaccines to more than a million Coloradoans. He also came out with the statewide measure Proposition 123, giving affordable housing to more citizens of the Centennial State. He’s also the CEO of Gary Community Ventures.

The biggest issue looming over the heads of every candidate has to be the homeless problem in the city, especially the encampments. The one quality both Johnston and Brough shared when it came to this subject was compassion; neither one feels that the “sweeps” are particularly humane. Also, both agree that the sweeps are useless as they just move the encampments down the street a few blocks, and have supported them being stopped. However, that’s where the similarities end, as each candidate has a precise idea of how to best resolve the homeless crisis.

Said Brough, “I would get people to safer locations. For me, what I would do is try to get everyone indoors, but we know we don’t have the housing and shelter we need today. So, I would temporarily sanction outdoor safe locations where we could take people immediately to get them to places that at least have running water, bathrooms, trash receptacles, and some security and safety where we could provide support and services that people so desperately need.” She continued, “And then I would work as a region to build the housing and shelter that we need—five city mayors have endorsed this plan in the metro area.” She then keys into an ideology that permeates most of her platform. “Working together I’d use data to drive our decisions and I’d focus on prevention—it’s less expensive and frankly easier than what we’re doing today. And for me, prevention is keeping people housed instead of people losing their housing and then we try to figure out how we help them after.”

With that said Johnston has a much different plan …

“I would build what I call micro-communities. You take half-acre vacant lots in the city and we put 40 to 50 tiny homes on those sites. They have heating, they have a locked door, they have beds, they have tables, they have desks, they have access to showers and bathrooms and kitchens. And you can get people out of encampments and from freezing to death into these communities. Then you can push in all the wrap-around services that do addiction treatment, that do workforce training, that do mental health support, that do long-term housing services to get people really back up on their feet and back into society. If you open up a new micro-community, you have 40 or 50 units there. You can go and you can move entire encampments, taking two or three blocks of the encampments and move those people to much more safe, stable, dignified housing where they can get back on their feet and get back into society.”

But can it work?

According to Johnston, most definitely. “We know that's worked very well because we’ve done it in Houston. When we did this as a pilot project we had about 300 units, and out of the 300 participants, more than 86% of them were still housed a year later; that shows this structure really works.” He also claims that no taxes will be raised to support his plans. “None of my proposals require more taxes; they’re all funded out of the current state and city budgets.”

Sadly, one of the systemic issues found in crime and homelessness is drug addiction. I wanted to know what plans or programs each candidate has when it came to tackling this issue.

Johnston’s plan comes in “two parts. One is we know the benefit of getting people that are unhoused moved into these micro-communities because, in each of these communities, they will have all of these wrap-around services where you can have addiction treatment you can have mental health support. That’s a much more efficient way to deliver services.” He continued, “[For] the severe cases; those people that have the most significant mental health needs or the most significant addiction needs—the ones still committing crimes and getting into trouble regularly—the ones not getting access to treatment services will also have options. What I would do is convert two pods of our county jail; one into inpatient mental health treatment and the other into inpatient addiction-based treatments. They’d get long-term service and care while they’re being helped [to get] transitioned back out into a community placement program. Then they can get a place to live at a job and medication and food and things they need to be successful.”

When I asked Brough the same question, it became apparent that her solutions are deeply motivated by life experience. “I have personal experience in this space; both as a former counselor for young women who’ve been adjudicated but also my husband struggled with an addiction our entire life together and my girls and I lost him.” Because of this, her solution is based on people building relationships with the people involved in the local community’s programs. “You have to build a relationship with people to help them be able to make the choice to get that support and those services. And that’s exactly what I’d continue to do. I think our nonprofit community does really good work in this space; the city has a number of outreach workers that I would continue to prioritize in helping people. And not just with addiction issues but, also with the mental health support that they need.” As someone who has struggled with addiction issues myself, I can testify that a positive, core support system is key to attaining some form of sobriety for someone trying to get clean.

Because both candidates know how addiction can destroy lives, I wanted to know about their plans when it comes to combating highly addictive substances—like the one I recently covered that goes by the name of “potions”—that are legally available and sold as “herbal supplements.” Would they opt for the route of public awareness, or would they go straight to legislation?

According to Brough, she would “really rely on experts to help us understand when we should be worried about crossing the line and whether we need legislation because of the risk it might pose. If needed, [we would look at] doing something different with public policy regarding it. And when it’s an education issue, then I would build a strategy based off of that.”

When asked, Johnston initially responded in a similar fashion, “You know I think we ought to look at all the above. I think we’ve got to do both. I think we’ve got to look into public awareness about them. If there are risks to people’s safety, then regulate them or even prohibit them.” But then he took it one step further, “you think about all these incredible vetting processes that all the cannabis products have to go through—ongoing very extensive testing—and I think we should expect that same kind of vetting for other products, and if those products aren’t meeting that criteria we should take action.”

One of the biggest pleas that come from those who struggle by existing paycheck-to-paycheck is how the minimum wage should be raised to a living wage. When I asked both candidates about this, they made it clear that in the current political climate, it isn’t likely to happen. Instead, they both pivoted to their plans when it came to affordable housing for the middle class.

Johnston’s plan is two-pronged, “When it comes to affordable housing, we put together a ballot measure. What this would do is build or convert 25,000 units to be permanently affordable. What that would mean is you would never pay more than 30% of your income to rent. So, if you’re making $40,000 a year, 30% of that is $12,000 a year, that’s $1000 a month in rent. You could be a single mom, a kindergarten teacher with two kids but your rent would never go up more than $1000 a month unless your income goes up. And that unit is ‘deed restricted,’ which means it will be affordable forever.” The second prong of his plan focuses on job placement. “We have a program we’re going to announce called Upskill Denver. This program means if you’re someone that’s working as a barista or as a server and you want to move into cyber security, or you want to move into being a nurse, or you want to move into a construction job, we can help you get access to training programs. You could get the training you need for those jobs without paying any upfront costs as well. The only time you pay is if you get a job that pays you more than $40,000 a year, then you repay about a third of the cost of training, the employer that hires you pays about 1/3 of it, and the city or philanthropy pays about 1/3 of it.”

Brough’s plan was a little more vague, focusing on currently available safety nets. “The place I think we might be able to have a greater impact on people’s quality of life is the cost of housing for the working class. Employers and government are starting to really think about ‘what is the role we play in making sure we have a range of housing options that are affordable?’ This might be the fastest way to impact and improve people’s quality of life and standard of living in our city.” She continued, “Frankly, part of me running for mayor is I feel a sense of pride about delivering a safety net that allows our residents to find their path and their opportunities. And if we’re honest, there isn’t a single person who doesn’t get help on some level. Today I’m the safety net for my own kids; I’m very proud to be that. My daughters need help just like everyone else. But sometimes we just need it from government and I don’t see a distinction.”

For anyone who follows politics, nothing a politician promises ever happens with 100% accuracy 100% of the time. With that said, I wanted to finish the interview by asking both candidates if they did get everything they wanted, what would Denver look like in a few years?

Said Brough, “We’re starting to address the inequities that we see in our educational system, where you know less than one in four of our kids of color are reading at grade level in 3rd grade. We’d start to see the inequities in homeownership (where it’s racial inequities we see) start to disappear. I think we’d start to see income differentials in all of our neighborhoods [disappear], where people are able to live in neighborhoods they never could have lived before, with kids able to access schools that we never could have gotten them to. What I would describe is we start to see how social capital actually, really works when you build a city with the intention to make it work. And that’s exactly what I would intend to do.”

According to Johnston, “For me, it’s three big things. One would be you would find that this is a city where all of the people who play critical roles in serving the city—teachers, nurses, firefighters, waitresses, kitchen staff—those people could all afford to live in Denver. The second would be that it’s also a city where your grandkids can be out in any neighborhood in Denver and they’re safe. If you’re on your patio on the 16th Street Mall and let your kids run around outside, to not worry about their safety. Number three would be that you can walk home from a Nuggets game at night, or from your restaurant at night, or walk back to your neighborhood and know there is nobody that has to sleep on the streets in Denver.”

By the end of this piece, I know there will be people who absolutely love Brough. I’m also aware that there will be those who are firmly going to place their support behind Johnston. For me … I’m completely divided. And unfortunately for me, the division comes from the fact that these two candidates make my brain fight itself.

Brough has completely captured my emotional core. Though not included in the direct quotes, we both spoke about our upbringing and how we were both on food stamps at one time and like her husband’s drug addiction, I too was shaped by the havoc that my addiction caused. It’s clear that her motivations are coming from someone who has “been there, done that,” and doesn’t want to see people go through the same trials she has.

Johnston has enraptured my logical core with his numbers. His ideas are clear and concise. He has the amounts figured out and where it’s going to come from to make his lofty ideas become reality.

And that one word, “lofty,” is why I think my decision will come down to one factor … can he get it done?

As I wrote earlier, no politician gets everything they want/promise. Brough’s entire political career has been in the city of Denver … her roots run deep. The fact that one of her programs has the support of five city mayors speaks volumes. Though her explanations may have been vague, she could have the connections to pull off more of her programs—while achieving the desired results—than Johnston could. The choice is really going to come down to who you think has more of the political capital necessary to see their programs realized.

Either way, it seems the city of Denver wins.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.