The good stuff ain’t cheap, and the cheap stuff ain’t good …

Call it #firstworldproblems, or whatever, but it’s an excruciating task having to find something better to do between seasons of your favorite show. As mass consumers of media — some 6,500 hours every year — Americans have become increasingly reliant on having things now, when we want them, no waiting. Which is doable for cravings of science-meat thrown on a cardboard bun with no nutritional value, but for some means of entertainment, it's often having to wait years before devouring the conclusion of a season-ending cliffhanger.

But why? Do networks hate their viewers to the point they actually enjoy torturing them for twisted pleasure? Maybe. But unlikely, considering those places need tons of cash to operate. Everything they do is to net the most viewers at any given time.

So why wait a year and a half between a Game of Thrones season six and seven? For the most part, it’s circumstantial, up to the executives and creators on whether or not they’d like to rush it through or piece together all necessary parts before delivering another incredible season. Fans are finicky, but they’re also unforgiving. It’s more beneficial to wait than release a quick, terrible product — an act that can destroy a popular brand.

Really, it has a lot to do with the way we consume media in the 21st century.

The structure in which shows are being made (and, unsurprisingly, how they’re being viewed) has changed exponentially in the past six years or so, or when home WiFi routers actually caught up with streaming capabilities.

Before that, it wasn’t uncommon for a season to write and film around 22 episodes (on average), often airing in the fall and having reruns take up the slot until a new season was released. Many regular television shows continue on this model, but it's quickly becoming outdated.

The template has been an industry standard for decades, heavily driven by Nielsen’s ratings schedule that began keeping tabs on viewers in the 1950s. Each year, there are 4-week periods that tally what people are watching around the U.S. — a time called “sweeps weeks” by the industry.

The higher the ratings, the more a network is able to charge for advertising (especially in the local markets). Often, TV shows in the past were (and today still are) built entirely around this system, bringing in guest stars, plot twists or generally anticipated episodes to boost ratings in specific weeks. Like everything else, the original television structure was driven by money.

But then came the streaming companies, screwing the whole thing up.

As media pushers like Netflix and Hulu began buying up certain rights to host copyrighted material on their dedicated platforms, analysts saw viewing habits change too. Instead of juggling multiple shows with specific nights on which to watch them, people were now consuming entire seasons in fewer sittings, blasting through brands within weeks.

“You see that over and over again,” says chief content officer for Netflix Ted Sarandos. “I’m sure more people watch ‘Portlandia’ on Netflix than ever see it on IFC. And they inch up their audience a little bit every time on the network. But for most people that’s a Netflix experience, not an IFC or an AMC experience.”

In a survey conducted by Netflix in 2014, 61 percent of viewers admitted to binge-watching shows regularly (2-3 episodes, or more, of a show in a single sitting) — and 79 percent claim viewing shows that way makes it better. Suddenly, older shows no longer being broadcast on regular TV saw themselves gaining new fans, and finally, people were given a way to catch up on shows that were hyped by peers without having to buy expensive, bulky DVD box-sets.

Championing this new experience the whole way was Netflix, a brand that was exclusively reliant on already made content in its earlier years. But as cash on hand grew, the idea of branching into exclusive content became reality. It's now what all streaming companies, including Hulu and Amazon Prime, are focusing on now. But as Sarandos says about its particular binge model, it’ll never follow the old television standard of making people wait an entire week for a new episode. It’s a company that drops all episodes as soon as it can.

“There’s no reason to release it weekly,” he adds. “The move away from appointment television is enormous. So why are you going to drag people back to something they’re abandoning in huge numbers?”

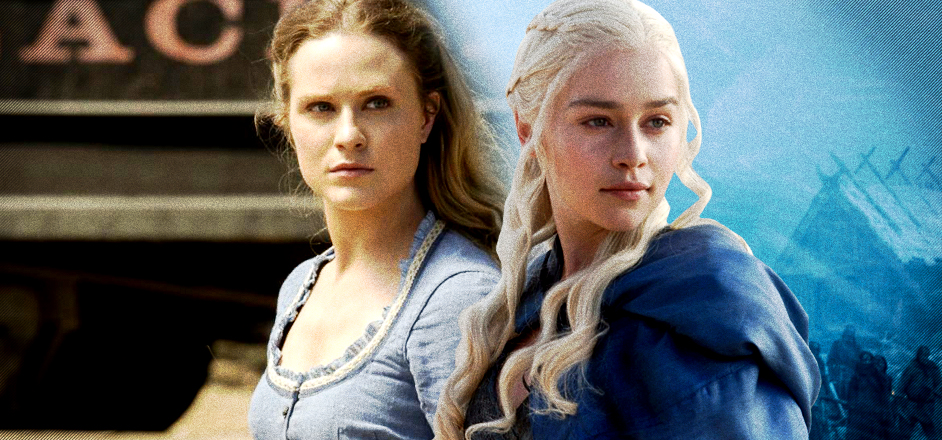

That’s not to say all platforms will follow the ideology of Netflix. HBO, and others, still drop an episode a week, and are successful in doing so. Westworld, HBO's latest cultural addiction, averaged 12 million viewers on all platforms for season one, surpassing even that of Game of Thrones (and setting a new record for the network).

One major aspect of the change is that the online world doesn’t have sweeps weeks. Platforms are in a continual battle for which outlet can garner the most eyes for any given show. With so many options and a finite number of viewers, it means networks are having to bring their A-game or get relentlessly washed behind whatever’s trending at the moment. There isn’t any opportunity to have a mediocre show and then bring in a guest star to boost ratings when they need to be boosted. Ad revenue is a 24-hour cycle, not a few weeks out of the year event.

Which makes it difficult to keep up with the viewer. Predictably, HBO would want a season seven of GOT to drop as soon as possible (or at a time when the viewer isn’t distracted with things like the presidential election or whatever else becomes all-consuming for no rational reason like Harambe). But in keeping true to the storyline, the season was actually pushed back a few months because of external conflicts, mainly the weather.

“Winter is here,” says GOT executive producers David Benioff and D.B. Weiss, “and that means that sunny weather doesn't really serve our purposes any more. So we kind of pushed everything down the line, so we could get some grim, grey weather even in the sunnier places that we shoot.”

What creators of that show also run into now, is that the script is completely written from scratch, given that author George R.R. Martin has only released five books of the series so far. Everyone involved has had to create every detail in the show for each season past number six — a more consuming means of creating episodes.

And as anyone can notice, production value has ramped up considerably from season one — adding in special effects of dragons, filming massive battle scenes and piecing together White Walkers simply takes longer. There’s not much anyone can do about it without forgoing value.

The gap between seasons also lends itself to where the focus of networks is at the time. Westworld was a predictable hit, one that the company rode while it could. Because of the attention being there, shows like The Leftovers (which hasn’t aired since Dec. 6, 2015) seems to have gotten snubbed. There are quick teasers before other shows claiming the new season is coming (and it’s readily admitted that in 2017 we can expect it), but it was never a huge hit for HBO, so the company rightfully backed off in lieu of championing its blockbusters.

So whether the time between seasons has to do with perception, based entirely around how we’re fed our favorites in bulk rather than not, or the actual creators of shows having to take more time around external influences, the rate at which we’re given our favorite shows likely isn't going to change anytime soon.

It’s contemporary media, a massive bucket of content vying for everyone’s precious time. But it’s not like we don’t have exorbitant numbers of products to consume in between seasons. Past episodes and series notwithstanding, there still continues to be an incredible amount of media being pushed from all platforms. Everyone wants their share of the market. The only way to do that is to have a good product — Business 101.

The good stuff ain’t cheap, and the cheap stuff ain’t good.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.