The art of ecstasy is the business of anonymous artist Chemical X. The UK-based virtuoso is pushing the boundaries of art as it’s known — depicting the gaudy, tripped-out style of rave culture with an utterly unique medium, one that has become synonymous with the EDM scene over the years, and one that gives his layered artwork a psychedelic edge.

Ecstasy pills. Thousands of them. Each one a pixel in a larger mosaic; each telling a story all its own.

His work balances on a strange and dangerous intersection: between contraband, art and music. Over the years he’s struggled with galleries losing their nerve to display his work and government agencies getting in the way of exhibitions. But he’s worked through and around all of it. And his art has become internationally famous because of it.

But these ecstasy masterpieces are just a few in his most current art series.

Chemical X has also worked on projects with Banksy, Damien Hirst, and Jamie Hewlett in the past. He created the logo for the Ministry of Sound (the UK’s “Home of Dance Music”), created logos for DJ legend Paul Oakenfield and hip-hop legend Snoop Dogg; he’s made art for Vans, Playstation, Coca-Cola, MTV, and even the BBC …

Chances are, at one point or another, in one form or another, you’ve come into contact with Chemical X’s art. Its bubbled up from the underground world of EDM raves, to infiltrate and saturate youth culture and lifestyle.

Still, almost nothing is known about the artist himself. In photos, Chemical X is always wearing a mask, sunglasses and a ball cap embossed with his logo. His website is an invitation-only cyber-space that will boot you if you try to get in without permission (with the message, “Not in those trainers, mate. If you are a serious punter you should look at this. No tyre kickers.”) His voice has never been heard. His face has never been seen. His true name, never revealed.

And he wants to keep it that way.

Which is why it was so tricky tracking him down — chasing enigmas is something like stalking shadows. But after some digging and a number of emails with his senior lab assistant, the enigmatic, anonymous artist agreed to an interview with Rooster Magazine — albeit over secured email (for obvious reasons). We talked about his artwork, his process, rave culture today and what it means to be a world famous anonymous ecstasy artist.

Ecstasy is not a typical art medium; where did your inspiration to use it come from?

"When the use of ecstasy went mainstream in the UK, it changed the way British society worked for a while and those changes will have repercussions forever. I believe it had a cultural impact akin to the use of LSD in California in the '60s. That influenced the way music, literature, fashion, art, free expression and society worked and, although it’s use dissipated over time, its impact resonates to this day. People who were around in the UK prior to the Second Summer of Love — which celebrates its 30th anniversary this year — will remember a landscape that was very tribal, where you could get your head kicked in for having the wrong haircut and alcohol was the only party drug apart from a bit of amphetamines and some shit resin. There was no love for strangers.

The emergence of ecstasy proved an incredibly creative period socially as people gathered together and were truly united by the way MDMA made you feel. If you look at videos of old UK raves you will see it is a total mash-up of people from a variety of ages, social status, sexual orientation, ethnic background and employment. I have raved with many an off-duty copper in my time and there are many, many people for whose ecstasy was their first and last foray into the illegal drug scene.

And amongst all this there were the pills themselves — not something that I think you have in the States so much — new designs would come onto the market, each with a rep for being a bit speedy, a total monger, a bit trippy, totally loved up or whatever. Rhubarb and custards, disco biscuits, doves, Mitsubishis, Adams, the list goes on. Getting your hands on a little bag of 3 or 4 of these would fill you with an anticipation, an excitement that made people want to have ‘an E shit’ before they even took them.

I wanted to capture that moment, to hold it in an eternity, to stop it in time and space where its potential would be forever held in suspended animation, no longer a drug but a memory or a future experience never to be fulfilled. The work had to have an aesthetic beauty first and foremost, an overall attractiveness like the idea of something is often more beautiful than the reality of the thing itself. Then, when you engage with the work up close there is a visceral response to being in such close proximity to something that will represent something different to each person that stands in front of it, depending entirely on their history, relationship and attitude to it.

I held a one-night-only show in London last year: 300 people, no one knew where it was until an hour before, Orbital on the decks, and the one word I heard more than any other that night was ‘Amazing’. If you can get that kind of response from people for your art, then it’s worth all the ball-ache around the medium used. People are genuinely excited to see it. Fatboy Slim told me he could feel his eye dilating just looking at it.

Ecstasy often affects artists and their artwork in dramatic ways; has it affected yours at all (besides being your medium of choice)?

I don’t think so per se. I am a product of that whole journey and I have specifically used pill designs from back in the day — I’m 54 now, but so are my contemporaries, and they have normal jobs, families, responsibilities but they also have the memories. If there was anything that affects my art it’s memories.

Do you have a Heisenberg-type chemist, who helps you get the right color, emblem and 'authenticity' in your pills?

Kind of. We have a studio and a lab. The studio perfects the colours, and the lab processes the final pills. I have an amazing woman who gets the colours just right and knows her way around a desktop pill press. We make sure that we are at arm's length from the lab though as we are visible and they are not. That said, we do have to make pieces that only contain replicas. Collectors are free to determine what goes into their commissioned pieces though.

The 'Prophets of Ecstasy' is one of our favorite pieces of yours; how long does it take you to complete a project like that, start to finish?

We are constantly making work that has never been made before, from working with UV powder to setting them in acrylic so things tend to take a lot longer when you have to make all of your learning mistakes on the job. The Prophets of Ecstasy probably took about 4 months to make — but the very first piece, Love & Death, took two years!

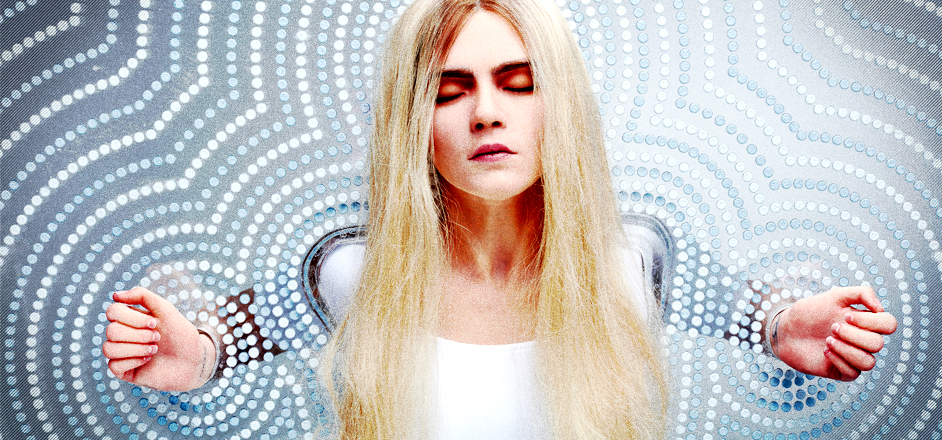

Would you explain the concept behind your latest piece 'The Spirit of Ecstasy' and what drove you to create it?

That was one that I had the idea for but I never thought it would ever get made. We only had 3 months to make it before the show and we were already making 12 other pieces at the same time, but the model had an opportunity to come to my collaborator Schoony’s studio to be scanned and cast and it was too good an opportunity to miss.

I based her pose on the painting "Ophelia" by Sir John Everett Millais and originally had her floating in the detritus of a nightclub floor, the way that someone can look like they are in trouble when they are, in fact, having a fantastic time inside themselves. I wanted to juxtapose the beauty of the model with the grime of the situation while making the ‘ecstasy’ beyond reach, in the mind of the model. However, despite my initial assumption that the model’s ‘brand’ and international status would preclude her from having any actual pills in the piece with her, she was insistent that if she was getting involved she was fucking getting involved and wanted to be surrounded by pills.

Initially I said that we would do both pieces and hang them facing each other — one the reality to the outside world and the other, the internal experience of the model, but we were so short of time and we had so many issues to overcome that we ended up just doing the pills one. The other might still happen one day and the pair will live as one piece.

What's it like being an internationally renowned anonymous artist? There has to be both perks and drawbacks to it.

The anonymity is not about the drugs actually, as this ecstasy series is just that (a series and my next show won’t contain any illegal substances). I’m anonymous because it forces the focus onto the art and not the artist. I don’t want to be judged on any work I’ve done before or who I am, people can’t help but judge Damien Hirts’s work based on their knowledge of him, if they have any, the same for Tracey Emin or Jeff Koons, Andy Warhol or Jean-Michel Basquiat. I know Banksy from back in the day and we could sit in a pub and have a pint without anyone bothering him and, despite his current omnipresence he can still do that. The people near you keep it quiet, no one wants to be the wanker that blabs. Besides, the idea of Banksy is far more exciting that the reality, it has to be. He’s an enigma and we all love an enigma.

You've been involved with rave culture pretty much since its genesis; how do you feel about where it’s at today/how far it’s come from those early years?

I’m not sure there is a rave culture anymore. In the States it’s become big business, ‘dance festivals’ get licensed, ‘raves’ don’t. Like punk rock needed glam rock to rebel against, so to rave culture was the opposite of mainstream clubs and their rules. Acceptance always takes away the excitement of rebelliousness and that is at the heart of rave culture. It was owned by the ravers and not ‘the man.’ That said, each generation needs a space to experiment and their first foray into the world of MDMA should be done in a positive and welcoming environment as it will often be an awakening from an emotionally suppressed teenage world into one where no one gives a fuck about how many fucking followers you have in Instagram, just to be in the moment and share the love for fuck’s sake!

Has e-currency made it easier to get your artwork to collectors?

The people that tend to buy art like mine using cryptocurrency tend to be big time drug dealers to be honest.

I know in the past you've had problems with gallery's getting cold feet and drug government agencies getting in the way of your exhibitions; do you still struggle with these kinds of issues?

It’s a constant thing but it has made me do things differently to other artists as I don’t show in galleries currently and I don’t sell work through auction. People buy my work through word of mouth and via social media weirdly. I fucking hate the art world with a passion so not having to give a gallery 50 percent of the sale price is always a bonus and if I can establish myself as an artist without feeling that I owe some cunt with a big white room and a little black book my success I’ll be happy. That said I expect that I will have to deal with them at some point.

Any new projects under way?

I’m in LA at the end of the month meeting with a wide variety of people to try and understand the place as my next show will be entitled ‘Fake’ and will be held somewhere in La La Land in a year or two. As an example, it will feature a portrait of Hugh Hefner made from fake Viagra pills bought off the Internet. For now, I am looking at how to introduce Chemical X to the USA without getting incarcerated for the rest of my life. If any of your readers have any ideas around that I’d be grateful to hear them.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.