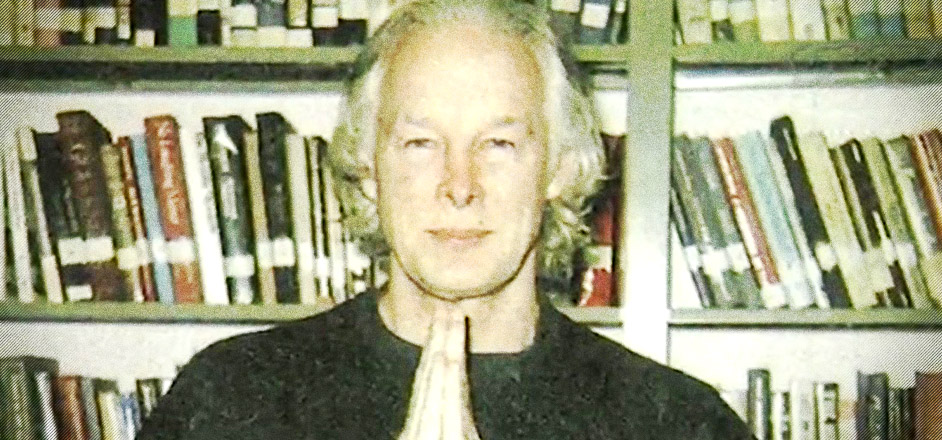

A man named William Leonard Pickard is now serving two life sentences in a maximum security prison in Arizona, a dull concrete space where no flowers grow.

Unlike most of the murderers, rapists and terrorists in with him, Leonard Pickard has fans — thousands of them — and they don't think what the government says he did was wrong.

Pickard is alleged to have been the largest LSD chemist in the country at one time. Ratted out by another chemist, Pickard was arrested outside a decommissioned missile silo in Kansas in 2000 with a truckful of lab equipment.

Rolling Stone called him The Acid King. Fans call his long sentence a massive injustice. Now, his fans are celebrating the book he wrote from a cell, called "The Rose of Paracelsus: On Secrets and Sacraments."

It's a crazy story of an international clan of secret LSD chemists who cook up millions of doses using elaborate clandestine methods. They live a fantastic lifestyle of high luxury and monastic poverty, daringly escaping detection and battling forces arrayed against them. They train ex-hippies to infiltrate the government to spy on the DEA. They perform magic and do telepathy and channel strange forces like sorcerers.

It's 650 pages of tiny print, thin margins, dense vocabulary and flowery, poetic language. But it's found an audience. Enough that it's being published in a second edition.

"A modern masterpiece," one fan says on Goodreads. "I plan on reading it again and taking notes this time," says a Reddit reviewer. "I am dumbfounded, and enthralled," says a reviewer on Amazon, where 97 percent of its reviews are five-star. "So surprised that there aren't more people discussing this work!" A fan called it "The Psychedelic Ulysses," after the greatest novel of the twentieth century.

So it's an underground hit. But some critics say they wish it wasn't such a tall tale. They want a true story of crime and punishment. Not all this woo and poetry and superheroes and fiction.

"Is it fiction?" Pickard asks, rhetorically, when I bring up this objection. "You know, it surprised me when people started saying this was fiction."

"I'm not at liberty to address whether it is or is not fiction due to legal issues," Pickard says. "You understand my predicament."

Pickard is appealing his conviction. He also asked me not to specify how we communicated — whether by phone, email, in person or by letter — because "there could be problems."

"Every individual who is named by name in 'The Rose' is locatable," Pickard goes on. "The professors, the people in D.C. … that sort of thing."

How often does "The Rose" intersect with reality? You'll go crazy trying to figure it out. The mystery of Leonard Pickard, the Acid King, is a bit like the mystery of psychedelics themselves. The deeper you look, the more confusing it gets.

FANS LOVE THE ACID KING

Pickard is known to be an amazing chemist. If he did cook up LSD, one online fan says, Pickard "deserves an award."

"We are increasingly finding that psychedelics have broad medical benefits, and perhaps even benefits to us as a species," says Julian Vayne, an author and speaker, and a fan and friend of Pickard. In clinical trials, for example, LSD has reduced anxiety. "There is a whole group of people who have benefitted from the substances he is alleged to have made."

So Vayne is one of dozens of people trying to help Pickard by getting more publicity for "The Rose." Others trying to get attention for the book include shamans, drug researchers, psychiatrists and mystics from around the world. There's a vague hope that Pickard's case could get attention. President Trump has pardoned nonviolent drug offenders before.

Can the book become truly popular? It's not easy to read. In word count, it's about one-third as long as the Bible. Pickard told me it can be read straight through in about 20 hours. But the vocabulary is so dense and arcane even an SAT champion reaches for a dictionary three times a page. The allusions and references are so thick that, to track down the hidden meanings and subtexts, could take you months of full-time work.

"It's not written for everyone," Pickard says. "It's written for very literate people that are familiar with the community and the experiences."

"He has written a really classic piece of literature," says friend, fan and podcast host Lorenzo Hagerty. "It's the story of his life in fable form, and the story of why he did what he did, about how it's not about money, it's about reintegrating these medicines into the fabric of society." Hagerty is helping plan a series of podcasts, reading "The Rose" chapter by chapter, posted on Hagerty's Psychedelic Salon. There have already been readings at psychedelic conferences and in the famous jail cell of Oscar Wilde.

"There's been some great psychedelic literature, and 'The Rose' is really high on that list," says Vayne. "And it's made more beautiful and terrible by the fact that it was written by a guy locked up in the middle of a desert who hasn't seen a tree in 20 years."

THE BACKSTORY

About 23 million Americans have taken LSD — about one in every 14 people. LSD isn't easy to make. So a lot of the LSD has been cooked up by groups working together. In the Sixties and Seventies, it was Augustus Owsley Stanley, Nick Sand and the rest of the "Brotherhood of Eternal Love."

Born in 1945 in Georgia, Pickard grew up the child of a lawyer and a professor. With a trust fund and a big imagination, Pickard wandered the country during the hippie Sixties. At some point, the feds believe, Pickard started working with the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, according to a 2001 profile of Pickard in Rolling Stone. By 1977 neighbors were reporting a funny smell coming from his California abode, and cops discovered a lab in the basement with traces of a psychedelic called MDA, similar to MDMA (ecstasy). Pickard served 18 months in prison.

A decade later, in 1988, a neighbor reported chemical smells from a California warehouse. Drug agents moved in, and (allegedly) found Pickard whipping up LSD. He might've made twenty million hits. Pickard was sentenced to eight years in jail.

Pickard was released early, in 1992. This is about when the "The Rose of Paracelsus" picks up the story. In real life and in the book, Pickard leaves prison to live as a monk in a Zen monastery in San Francisco. There he meditated and chanted. According to the book, Pickard went clean.

Pickard managed to get accepted at Harvard, a place full of nobel prize winners and former Senators. Pickard really did become a drug researcher, looking not into psychedelics, but deadly drugs — particularly fentanyl. And he really did publish prescient papers on fent.

According to the book, Pickard was, at the same time, also interviewing a network of six underground LSD chemists, to learn their secrets. The book tries to keep Pickard's hands clean, by saying he was merely doing research. According to the feds, he was cooking LSD right along with them.

AND HERE'S WHERE THE BOOK GETS SUPER MURKY

It's frustrating to try to figure out the truth. But what's most interesting is letting your mind wander to the idea that part of what he's saying about drug chemists is true.

If the book is partly nonfiction … then there was, and possibly still is, a clandestine worldwide network of LSD chemists, like a Justice League or a League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, who manufacture the drugs at secure locations around the globe, then dismantle the labs and shlep them to new hideouts. The chemists keep up on the newest developments in novel drugs. They treat their syntheses as sacred acts. Hippies who love drugs cut their hair and don suits and infiltrate the DEA as double agents, as spies keeping the chemists one step ahead of the cops. Or else they use beautiful women to seduce governmental agents to see what they know. The chemists police themselves, so that if a new chemist with bad intentions sets up shop and starts making drugs, they step in and shut him down. (The book implies that that's why Pickard went to Kansas; he was acting on behalf of the LSD chemists to close down the operations of another drug chemist, Todd Skinner, a man who was actually a DEA informant, and turned Pickard in.)

Pickard's portrait of the chemists is pure romance, painting the chemists in bright, vibrant colors, as noble rebels for a cause, erudite and urbane, able to quote poetry and law and Sasha Shulgin in the same breath, dashing men in a world of deep connective sex with beautiful young women (usually with "small, pert breasts") and girls they often rescue from cruel, feckless pimps, with wealthy patrons loaning them space and giving them money, with spiritual teachers reminding them always that LSD is a gateway to heaven or hell, not just a party drug — heroes out to synthesize a potion that could save humanity from our slide into disconnection and environmental disaster.

In the book, these chemists are "revolutionaries in times of oppression" who "pray for an end to suffering" by cooking "fountains of consciousness" in "planetary scale batches," and therefore have "responsibilities for the ecstasies, the orgasmic religiosities in millions of minds."

"Psychedelics displace addictive drug use," a chemist says. LSD, one says, is "the polar opposite of a nuclear bomb."

THE MAGIC IN 'THE ROSE'

And, then, the strangest assertions. If the book is nonfiction, then LSD chemists can do magic. They're surrounded by "paranormal phenomena." They have "hypersensitivity," "a new human sense." "It would be naive to conclude there are no unknown extra dimensional fields," one of the chemists says to the narrator. They do telepathy, changing the narrator's thoughts with their thoughts.

Fans of the book love these ideas; everyday trippers often report telepathy — two people thinking the same thoughts, seeing the same hallucinations. (A misperception, rationalists say. You're just stoned.)

The chemists swim in synchronicity: the right person shows up at the right moment, there is order to events, direction; Nature is trying to accomplish a mission. Again, typical stoners often have this feeling. (Over-recognition of patterns, realists say. Lower your dose.)

The chemists deal with spirits; they ask otherworldly entities to bless their syntheses; they ritually pull demons out of the bodies of drug addicted young women. Again, regular 'heads sometimes feel around them entities not entirely of themselves. (Remnants of medieval superstition, skeptics say. Stone age irrationality. You're just high.)

Does Pickard believe this stuff? Is this how high-level LSD chemists think? As usual, Pickard plays coy.

"Some of the scenes are so unusual — the exorcisms for example — that if they were factual, people who gave it credence might lose a little sleep dealing with the philosophy of it, the theology of it," Pickard says.

"It would take away the pleasure of wondering, is it fact or fiction," Pickard says. "I will leave the reader to decide for themselves."

A MONUMENT

Of course, Pickard has every motive to play this romantic song, to lionize the chemists, to play up the magic. Who doesn't want to be seen as part of a secret society, in touch with greater forces, and a martyr for a great cause?

Pickard's fans love "The Rose" in part because, to them, LSD is a kind of miracle, and acid chemists are kind of alchemists, and magic really is possible.

"This book is like the psychedelic state — inexpressible," says Vayne. "We have to talk about things in poetic or metaphorical or mystical terms."

There is a hint at the end of the book that Pickard, the narrator, is a chemist, too. Maybe actually all of the chemists.

"Some people say that the Six are just a single individual whose personality has been spit five ways," Pickard says. "I can't respond to that."

How Pickard is viewed in the light of history probably hinges not necessarily on figuring out exactly what he did or didn't do, but on whether regular people end up viewing LSD and psychedelics as benefits to society, or as curses.

Would the world be a better place, I ask Pickard, if everyone took LSD?

"I can't talk from personal experience," Pickard says, ever cagey. "I can only talk about what the literature reports. It does report about 80 percent come back discussing religious or magical experiences that are transformative in a positive way."

Someday in the future, someone might build a statue to the underground LSD chemists, near Haight Ashbury or Boulder, wild-haired dreamers peering into a beaker or flask. One-time criminals now romanticised. After all, there are statues to Harriet Tubman all over the place. Until those statues come, "The Rose of Paracelsus" is a decent monument to the LSD Underground — even if only a tenth of it is true.

Leave a Reply