Teresa Egbert wants to legalize magic mushrooms in Colorado.

"It's not just giggles," said Egbert, a mycology student and entrepreneur.

After sexual violence left her struggling with PTSD, Egbert said, "mushrooms gave me the feeling that I'm worth something. It's like a restart."

On its own, the state legislature won't ever legalize this obscure drug many people think belongs in the 1960s or at a Dead concert or that makes you go crazy. So Egbert wants a citizen vote.

She's spent months "being the hype man for mushrooms," as she says. Talking to friends, printing up campaign materials — stickers and buttons reading "Colorado for Psilocybin" — connecting with mushrooms lovers who are also veterans for the sympathy factor, and for the Fox News crowd.

And when Egbert started reaching out across Colorado in recent weeks, she was in for a surprise. Turns out, her group wasn't the only one working toward a vote on mushrooms.

There were at least two other psilocybin legalization efforts besides hers in the state.

Legalization efforts have already been in the works in two other states. Oregon hopes to legalize them for medicinal use, and California for all adults. Mushrooms are clearly also in the air in Denver. And Egbert seemed to be bubbling over.

"All these people were already thinking about it at the same time," Egbert said. "Synchronicity. Colorado. I love it."

One group wants an initiative in the city of Denver — not the whole state — and aims to have it on the ballot in November of this year, 2018.

Though the idea is likely to change and has a long road before it's on the ballot, the group's idea is basically this: give Denverites the right to grow, possess, use and give away mushrooms without fear of city cops.

You couldn't sell or buy them. But it would create space for spiritual use by shamans, therapeutic use by medical professionals and research. And, yes, plain old-fashioned adult use at the botanic gardens and the art museum.

"Psilocybin can be a really powerful tool," said Denver's Tyler Jay Williams, who is among those leading the effort. "And it's relatively safe compared to other drugs."

His group met recently in an event hosted by the Psychedelic Club of Denver, for which Williams is the treasurer, in a low-lit, low-ceilinged basement of the Hooked on Colfax coffee shop reminiscent of a speakeasy in the 1920s. Fifty or so people, from crystal-wearing tie-dyed folks to lawyers in suit jackets, arrived with stories of how mushrooms treated their nerve pain, "changed my life," "reset my brain" and "snapped me out of a depression."

To the meeting they brought tons of expertise on legalizing drugs, which they'd learned during the fight to legalize cannabis. Lawyers from cannabis firms were there. The former head of the Marijuana Industry Group. Williams was involved the successful city campaign to legalize the social use of marijuana. They shared information about ballot deadlines, costs, strategies. Lawyers and political activists in the crowd agreed to form a committee to draft ballot language that will stand up to legal scrutiny.

Mushrooms aren't as widely used as cannabis, alcohol or many other drugs. And they're also not much of a legal problem. Denver cops made only 181 busts for hallucinogens of all kinds last year, a category which includes not just mushrooms but LSD, DMT, peyote and other psychedelics. Compare that to the roughly 3,000 busts for heroin and 4,000 for cocaine.

Evidence shows mushrooms are one of the safest drugs physically — safer than alcohol — and difficult to get addicted to. Studies show they treat migraines, depression, and end-of-life anxiety. About twenty million Americans have tried mushrooms, and millennials are doing them at about the same rates as baby boomers did them in the Sixties.

Legalizing mushrooms, though, doesn't sit well with Jo McGuire, president of the board for the National Drug and Alcohol Screening Association, which advocates for safe and drug-free workplaces and communities.

"It's a completely ridiculous notion," McGuire said.

McGuire said she understands that mushrooms have therapeutic and spiritual value to some people, but she also knows that difficult mushroom trips can throw unstable people for a loop.

"You're going to have people getting a hold of these things who can't handle it, freak out, and next thing you know we have all kinds of accidents and injuries," McGuire said. "You're going to cause people that already have mental health issues to have a bigger problem."

Teresa Egbert, the woman who treated her PTSD with mushrooms, is now throwing her support behind the Denver effort.

It will need all the help it can get, especially to gather the more than 5,000 valid signatures necessary. Political strategist Emmett Reistroffer, one of the authors of the marijuana social-use campaign, estimates that a professional campaign to get those signatures would cost $50,000. Alternately, Chris Chiari, a former candidate for Denver City Council, said it could be done by perhaps 30 full-time volunteer signature gatherers.

Even if the effort fails, Egbert is excited there is at least one more organized effort in Colorado.

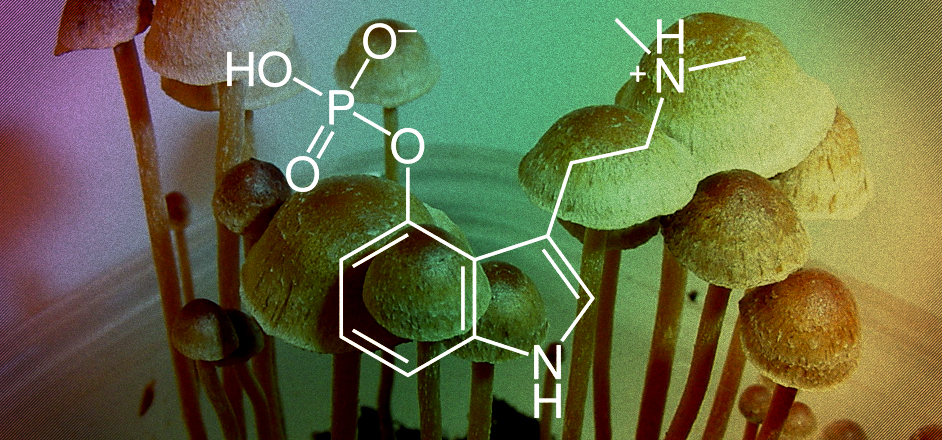

A different group calling itself the Colorado Psilocybin Initiative is aiming at a vote from all Coloradans — not just Denverites — in 2019 or 2020. And they're looking to legalize not mushrooms themselves but psilocybin, one of the active ingredients in mushrooms, which can be synthesized.

The group's leadership includes an entrepreneur, a mental health professional in training and a lawyer. They told us that they're carefully drafting and reviewing the initiative before going public in six or nine months. They asked us to keep their names private until then.

Their goal is to create a system of therapeutic use. Psilocybin wouldn't be legal for everyone. You couldn't grow your own mushrooms. Psilocybin would be meant for use under the supervision of a professional. This is more or less the protocol for the famous psilocybin studies at Johns Hopkins, upon which much of the enthusiasm for legal psilocybin is based.

"There is a growing body of research that shows psilocybin's benefits for treating depression and end of life anxiety, and it's a very safe substance when used in the right setting," one of the group's leaders told us.

Getting a measure on the statewide ballot is much more difficult than a city initiative, and requires collecting about 100,000 valid signatures from every corner of the state — even from farming and ranching areas unlikely to have strong opinions about an obscure drug.

Nationwide, support for legalizing any drug besides cannabis is low. In a 2016 survey, only about 20 percent of people support decriminalizing mushrooms.

Denver is not like the rest of the country, though. And the folks pushing for mushroom legalization in Colorado say that the case for legalizing psilocybin is at least as strong as it was for marijuana.

"Mushrooms just get you out of those bad thought processes, and they remind you how beautiful life is, how beautiful the world is," said Teresa Egbert, the woman with PTSD who believes mushrooms saved her life. "I don't think many people know about that. It's not a joke."

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.