Two guys with a purpose are hoping it will …

It's hard on everyone when opioids claim another life.

First the addict dies, then the friends and relatives are stuck suffering from the shame of what happens next. For the people left behind, there comes only two options: curl up and pretend it never happened, or spend the rest of their lives changing the ‘junkie narrative’ to help that it gets better.

"It's kind of shameful," says Jeremiah Lindemann. His brother, J.T., died 9 years ago, at the age of 23, after years spent falling in and out of rehab, getting oxycontin from pill mill doctors and from neighbors' medicine cabinets. Jeremiah didn't talk about J.T.'s death for a few years afterward. "I think everyone feels guilty,” says Jeremiah, now 39. “Especially for parents, they feel like they did something wrong. There is always a sense of, could I have done more?"

Opioid shame affects an astonishing number of people these days, as the country continues to suffer the throes of an "epidemic of drug overdose deaths" — as the government calls it. Opioids — which includes both heroin and prescription pain pills, which are basically the same drug — killed more than 33,000 people in 2015 alone.

That's about how many people died in car crashes. But, unlike car crash victims, who are often seen as innocent sufferers of an unfortunate accident, and who get roadside memorials piled with flowers and notes, opioid addicts get dissed and scorned for their behavior.

"Society teaches us to treat people who get addicted to drugs like shit," says Eric Pieper, 30. He says he was addicted to heroin for eight years, at times shooting up 2 grams of it everyday, along with 2 grams of cocaine. "And that's the reason it's so hard to get better, because you get treated like shit."

But that shame may be starting to lift.

Lindemann and Pieper are part of a growing movement to humanize opioid addicts. Across the country, projects like theirs are popping up with the same mission, which is to portray them as people, rather than criminal fiends: artists are taking humanizing pictures of heroin addicts, playwrights are writing plays humanizing them, and filmmakers are capturing the pain that comes from living with the stigma of addiction to opioids, and more and more people are posting about their dead loved ones on Facebook.

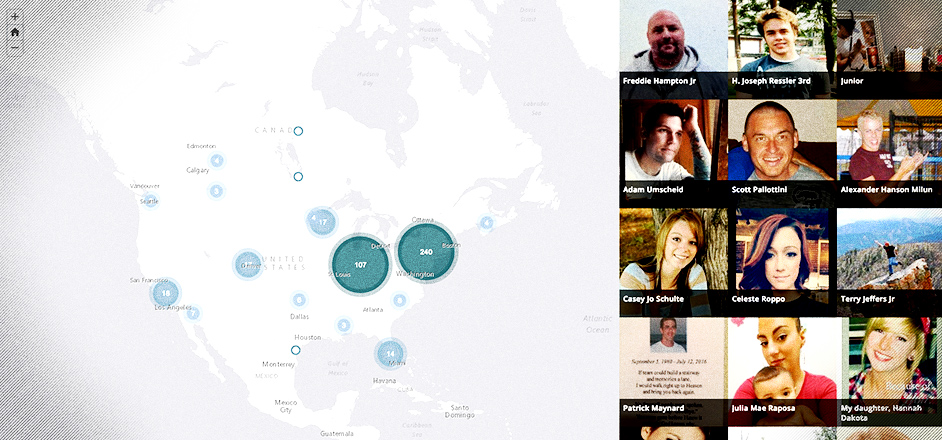

Lindemann had once tried to help the opioid crisis by volunteering at a rehab center. Then he realized he might have a bigger impact by using his mapping and computer skills. So he started a website showing the locations where opioid overdoses happen. It's called Celebrating Lost Loved Ones to the Opioid Epidemic. He’s made it easy for anyone to upload a photo, along with a story, of the deceased. Hundreds of people have already done it.

It's a fascinating and enlightening read. The shared memories the dead show that opioid addicts aren't all scraggly homeless zombies living in gutters, as most would stereotype them. The archive is full of mostly bright, happy-looking young people from the suburbs, riding wakeboards and climbing mountains and playing guitar like everyone else. It shows that opium stalks all different kinds of people. Not just people on the streets.

The response to his site has been great, Lindemann says. Families have come to him in support, saying that, "it's good to know that I'm not alone."

Pieper, for his part, says the opioid epidemic isn't a sad memory, it's an everyday part of his reality. "Somebody that I love dies at a rate of about once a month because of opioids," he admits. After injuring his big toe fighting in judo tournaments, Pieper was prescribed percocet, which started him down his path to addiction.

Despite continuing disrespect toward addicts, Pieper is seeing the conversation around opioids change, in part as a result of the humanizing efforts. "That's the only reason things are changing, is because upper middle class white kids like me are getting into (opioids),” he adds.

Pieper has also started a podcast called EenigmaRadio, which often deals with the struggle of opioid addicts and the broken medical system that is still getting people hooked on them. Pieper says he's clean now, with the help of natural medicines like kratom. He uses his platform to spread his message to others. "That's why I'm on this mission," Pieper says. "The guilt is what destroys most of us."

The stigma around opioid deaths is still solid. But efforts like these might be lightening it. And there may come a day when opioid deaths are less difficult. And — who knows — maybe they'll even start to happen less.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.