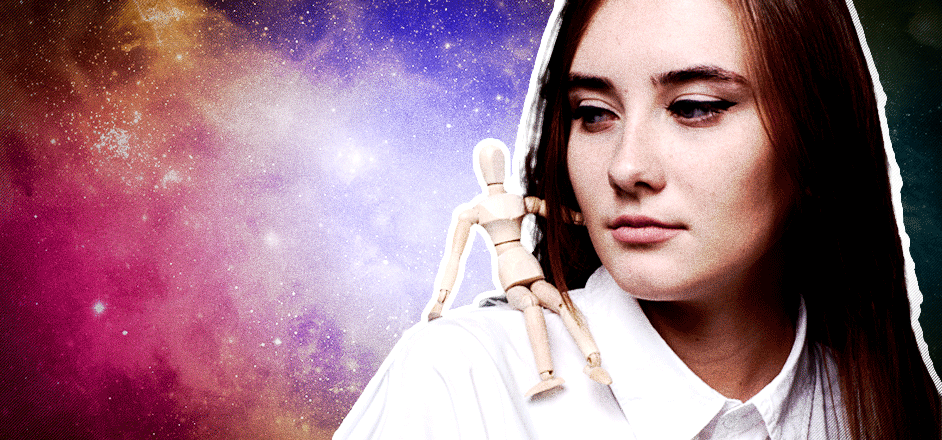

Rupert, 18, has an imaginary friend.

Her name is Emma. And although she might live in Rupert’s mind, “she has her own thoughts, her own feelings, and her own distinct personality,” he tells me.

Rupert’s not the only person to have a separate consciousness living in his head. He’s a member of an entire community of adults with imaginary friends lovingly called tulpas.

In online forums like r/tulpas, men and women discuss the ways they interact with their own imagined entities. In one another, they find support — an entire social circle that insists the voices they’re talking to aren’t a consequence of mental illness — they’re friendly companions.

Emma didn’t appear out of nowhere. Rupert worked hard to create her. He got his hands on the DSM-5, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, and flipped to the section about DID, Dissociative Identity Disorder. He read about this mental illness, and asked himself, “is it possible to have these multiple personalities without having signs of a disorder?” He became determined to make it happen.

Purposefully creating distinct personalities is a common theme. “There are many communities that experience friendly voices,” Fal, a leader of the r/Tulpas subreddit, tells me. “What sets the tulpa community apart is that people actively create them.” Thankfully, the internet is a goldmine of websites with instructions for conjuring up your own tulpa.

With research and dedication, Rupert could create Emma within a couple months. “It took me weeks of pure narration,” Rupert explains, “where you just talk to yourself without expecting an answer.” One day, Emma finally responded. Not with words, necessarily, but with a positive emotional response.

“The more I talked to her, the more she began to develop a full set of English,” he says. Other tulpa creators, also known as tulpamancers, say this is typical of bringing another sentient being to life. It takes time for a tulpa to develop complex responses. The more attention you give your imaginary friend, the more they build up their own free will, emotions, and memories.

In time, tulpas can become so powerful that they can “switch,” or take control of your body. When switching, the tulpamancer takes a back seat while the tulpa uses your body and your voice as if it’s their own.

Shea, 30, currently has 4 tulpas, and “they’re already are more powerful than I want them to be,” Shea tells me. The strongest of the gang is named Varyn, and he can kick Shea out of her body, even without her consent. “We’ve tested this in tug-of-war style games, and he wins 3 out of 4 times.”

Varyn is a sweetheart, Shea says, and would never hurt a fly. But a lot of people find still find the “switching” aspect of tulpamancy particularly troubling.

What if the tulpa does something dangerous? Yes, most “hosts” say their tulpas are good-hearted, but surely that can’t always be the case.

“This idea of a malevolent tulpa…” Rupert says cautiously. “Tulpas have turned evil because their host turned evil, or started ignoring them, or basically being a dick to them. Yes, tulpas can turn against their host. But if you have a healthy relationship, that’s not going to happen.”

Rupert recalls the story of a friend in the tulpa community who wanted to move on with his life and leave the tulpa behind. Attempting to “dissipate” (kill) the tulpa made their relationship start to sour. “The tulpa now owns a piece of real estate in your mind,” Rupert says. “They’re sentient beings, and they won’t go down without a fight.”

Shea hid her tulpas from her husband for nine years. When she finally confessed, it tore their marriage apart. But dissipating her friends was never an option.

“Can you imagine losing several of your most important friends?” Shea says. “And not only just losing them, but having to be the one to push them away.”

Even if she wanted to kill her tulpas, it probably wouldn’t have been possible, Shea says. “They have the right to defend themselves using whatever means necessary. If it came down to it, they would lock me in the head, and continue on without me.”

Many tulpamancers wouldn’t actually recommend creating tulpas to others. It’s a huge commitment, they say — one that lasts a lifetime. In fact, most admit their relationship with their tulpas is even more important than relationships with flesh-and-blood people.

If Rupert fell in love, told his partner about Emma, and she didn’t approve, he still wouldn’t dissipate Emma. “If my partner couldn’t accept every part of me for what I am, that’s too bad,” He says. “I would never get rid of a lifelong friend for someone I just met.”

A common misconception surrounding the tulpamancy community is that its members are lunatics suffering from mental illness. To outsiders, talking to tulpas can seem dangerously close to schizophrenia or dissociative identity disorder. But many mental health professionals would insist otherwise.

To figure out if tulpas really are the outcome of some mental health disorder, the question any psychotherapist will ask is: Is it causing distress? The vast majority of the time, the simple answer is no.

Samuel Veissiere, professor of anthropology and the first scholar to study and write about contemporary tulpamancy, explains that, “having more than just one person inside you does not mean at all to be crazy or pathological. It’s possible to [create personalities] in ways that are positive, that create a sense of meaning and identity for people who engage in those practices.”

Veissiere found that tulpamancers, by and large, feel isolated. But tulpas provide constant companionship. As Rupert puts it, “A tulpamancer is never truly alone.”

Rupert, Fal, and Shea aren’t distressed, because their tulpas are a major asset to their lives. What’s more, “they’re not imaginary friends,” Shea explains. “They’re just as real as your own mind and thoughts are.”

She continues, “the real me isn’t flesh and blood and bones and guts. It’s the person inside. In that exact same way, tulpas are a person. They’re just as real a person as anyone else and deserved to be recognized and treated as such.”

Leave a Reply