“No person … shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself …”

It’s a criminal’s favorite constitutional amendment, The Fifth. It protects the guilty from being forced to self-incriminate. And, it also protects the innocent from being unjustly molested by the law. The Fifth Amendment is a legal shield for The People, from the judicial branch – essentially protecting us from having to snitch on ourselves.

Rights like these are what make America such a special place. We’re all innocent until proven guilty, no matter how guilty we are or what it is we might be guilty of; and until we are proven guilty, we ain’t gotta tell you shiiii-et, Officer.

But with technology advancing at the rate it is, legal loopholes are opening up in this once watertight safeguard, that threaten the freedom of anyone who uses a smartphone (which, according to data from 2016, is about 250 million Americans). The fuzz is getting crafty and it’s bad news for American privacy.

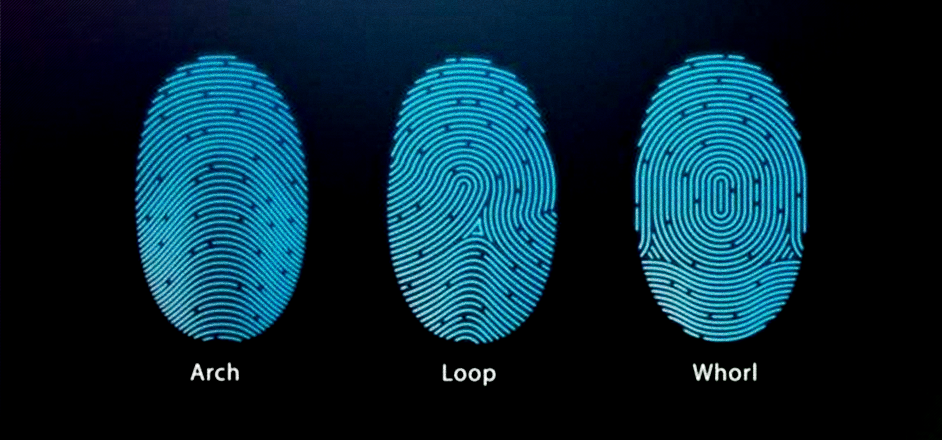

Let’s back up for a second, though. Remember in 2013, when Apple rolled out their fingerprint recognition technology? That sweet little feature that allows users to unlock their phone with just a scan of the fingertip? It’s an insanely convenient thing. It protects your phone from unwelcome eyes while at the same time making it quick and easy to open the device.

And it feels pretty futuristic, too.

Unfortunately, with futuristic technology comes futuristic problems. And, because your fingerprint isn’t technically “information”, recent legal cases have concluded that it isn’t protected by the Fifth Amendment. It is a thing and not a fact, so police can take it from you without your permission.

At least, that has been the rationale of several judges since this technology became available.

In 2014 (only one year after the release of fingerprint recognition tech), a Virginia Circuit Court ruled that, while police cannot force suspects to give up passwords, pins, or other information that could lead to self-incrimination, they can force people to unlock their phone with their fingerprint.

Then, in 2016, another judge actually ordered a California woman to relinquish her fingerprints so police could unlock her phone against her will. He issued a warrant which was executed within 19 days of the order – which is unusually fast.

While these cases remain relatively rare (as of now) they outline a particularly difficult issue that our legal system is going to be forced to grapple with very soon: the rapid acceleration of technology in society. The people who wrote the Fifth Amendment back in 1789 couldn’t have possibly imagined developments like fingerprint recognition and how it could affect legal prosecutions. The game is changing and it is doing so very quickly – far faster than the American legal system is equipped to handle. Which means that, innocent, innocuous-seeming technology could tear open gaping holes in our democracy, exposing our freedoms and leaving The People vulnerable to abuse by Big Brother.

Ye gods. Where is this strange road leading us? Because, technology like fingerprint recognition is getting more commonplace with every new wave of smartphone – facial recognition, voice recognition, retina recognition… this stuff isn’t going away. And if cops and courts are misusing it to exploit people for information they have no right to access, what does it mean for our society?

Well, not all legal scholars agree with the way this development is headed. Some, like Albert Gidari, the director of privacy for Stanford University’s Center for Internet and Society, think that the very act of unlocking your phone should be protected, even if your fingerprint itself is not.

Gidari told the Atlantic, “When you put your fingerprint on the phone, you’re actually communicating something … You’re saying, ‘Hi, it’s me. Please open up.’” Because using a fingerprint is a way of communicating with your device, Gidari believes that the Fifth Amendment should still apply to it.

So, maybe there is hope. Maybe, the American legal system is agile and flexible and lenient enough to catch and handle this problem and others like it before they morph into something larger and more ferocious. Maybe. Or perhaps we will just have to sacrifice certain rights and freedoms, in exchange for futuristic conveniences like these.

And people gladly will.

After all, no one is going to punch in a four-digit pin every time they need to check a text message – that’s just simply too much to ask.

Leave a Reply