Every day, when Stan Mastrantonis woke up under the rising South African sun, he would dawn his gear, eat a meager breakfast with his team, shoulder a semi-automatic weapon and get ready to get dropped off for his daily 20-kilometer patrol. He and the other game bodyguards in his team, would comb the bush looking for tire tracks or footprints, signs of poachers who may have snuck onto the Olifants River Reserve during the night.

Sometimes, when they found tracks, they would trace them, follow them and catch the poachers who had left them behind.

Other times, though, they’d arrive too late. In those instances, Mastrantonis’ patrol would happen upon a grisly scene of mutilation: of butchered rhinos and slain elephants, robbed of their ivory, bloody, hacked up and left to rot.

“It was exciting,” Mastrantonis says. “But it was depressing and challenging as well.”

An ugly scene that Stan Mastrantonis would see regularly as an African game bodyguard.

An ugly scene that Stan Mastrantonis would see regularly as an African game bodyguard.

Mastrantois is a South African native, who now lives in Australia with his wife and is getting his Ph.D in Ecological and geographic modelling at the University of Western Australia. He and I met under some strange circumstances in Perth, Australia, only months before he was shipping off to the savannah, to wield machine guns, hunt poachers and protect some of the most endangered and incredible creatures on the planet.

When Stan told me this was what he was going to do, I imagined him living an action packed adventure: tailing rhinos and elephants like a shadow, engaging poachers in violent fire fights and high speed jeep chases, tearing across the African savannah, literally fighting to keep these dwindling creatures safe from evil-doers.

However, Stan made it pretty clear that the job of a game bodyguard in Africa is not what most people imagine. It’s a lot harder, more complex, nuanced and even sadder than most people realize.

“The fact is, you can't really do much in terms of actually preventing the poaching,” Mastrantonis says. “You're really more of a deterrent.”

Originally, Mastrantonis had applied to become a game bodyguard because a friend of his wanted to do it with him. Stan agreed, they applied together, they were accepted, and then his friend bailed at the last second. But Mastrantonis pushed on — he’d made a commitment and he was going to follow through on it.

In no time at all he was slogging through a brutal six-week anti-poaching training camp, preparing for one of the toughest jobs he’d even taken on.

Mastrantonis was protecting animals on the Balule Private Game Reserve, which is within the larger Olifant River Game Reserve. It’s an area of over 100,000 acres of open savannah, of wild country occupied by wild animals: leopards, lions, hyenas, honey badgers, yellow billed ox peckers, Cape clawless otters, Pel’s fishing owls, Sharpe’s grysboks, rhinos and, of course, elephants. Stan encountered many of these creatures during his time out there.

In fact, he tells me, that dangerous encounters with animals were far more common than dangerous encounters with poachers.

“That was almost like a prominent weekly thing, you'd have some kind of animal encounter especially with elephants,” Mastrantonis says. “They're really very aggressive creatures, incredibly aggressive. And they don’t like humans being around.”

The perimeter of the Balule Reserve is largely unfenced and there are only two Anti-Poaching Units (APU’s) made up of 30 rangers each, to cover and protect the entire reserve. Meaning, poachers often come and go as easily as the animals do, under the cover of nightfall.

“It's incredibly difficult to find them because they're always coming at night,” Mastrantonis says. “So you can't really find people in that kind of thick bush. At night it's almost impossible.”

Which is why they look for their tracks in the daytime, when they go out for their daily patrol. It’s their best shot at actually finding these sneaky bastards on such a massive wildlife reserve, their only real hope of slowing the never-ending onslaught of poachers pouring in.

“If they’re caught dead, they'll often run,” says Mastrantonis. “But then obviously they would just give up after a while because we'd have cars and G.P.S. and helicopters and better weapons that were actually designed to deal with security, not with just for killing animals.”

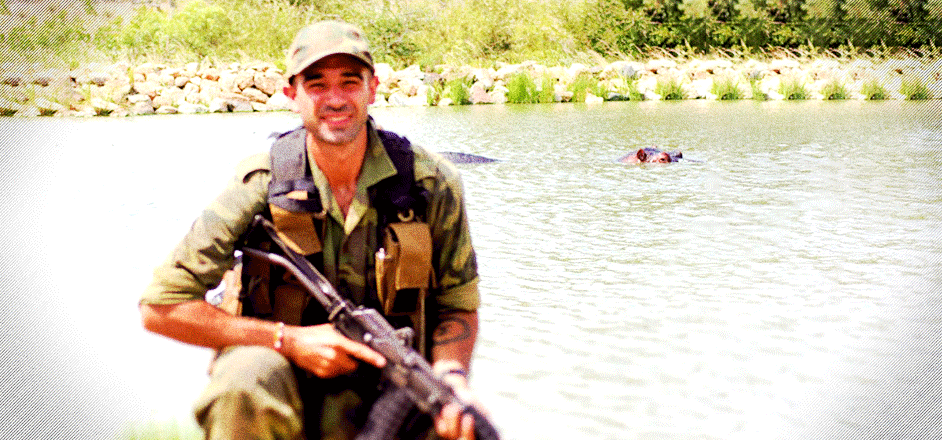

Stan and a fellow game bodyguard.

Stan and a fellow game bodyguard.

Many poachers would be successful, though. And while some would get caught, Mastrantonis admits that it's kind of a rarity.

“You still definitely catch the poachers but, more often than not you don't.”

It’s a big reason why Stan didn’t want to continue on out there, as a game bodyguard. He put in just over nine months before he decided it was time to call it quits. Because, as he explained, even the feeling of triumph that came with successfully catching a group of poachers, was quickly swept away by a strange sense of sadness.

“They're not evil, they’re just desperate people, they just want to get paid,” says Stan. “You know there's no work in South Africa, some of them are just trying to feed their family. A lot of them won't even do it for money, they’re going into the reserve just to get some meat.”

Most of the poachers he caught were desperately poor people, some of whom were just hunting elephants and rhinos for food and not necessarily for their ivory horns and tusks.

But even the ones that were poaching ivory, hacking the tusks and horns from innocent animals, even if they were caught and sent to prison, they might be out and back at it in a month, a week or even a few days’ time. The prisons in South Africa are so overburdened and the government so corrupt, Stan says that most poachers only disappear behind bars for a little while before they’re back out poaching again.

“There’s not that kind of conservation priority when you’re that desperate,” Stan says. From afar, in 1st world places like America and Australia, it’s easy to be outraged by these people out there senselessly killing endangered wild animals. “But those guys in South Africa, they don't really care that much because they just want to get some food.”

Simply put: their priorities are different. Poachers are thinking about survival; about feeding themselves and their children. So, when they see an elephant walking around they don’t see a majestic, endangered creature, they don’t hear David Attenborough talking about the sensitivity of this beautiful species.

They see a walking meat-locker and an ivory paycheck with a pulse.

Understanding that context, within which these people live is important to understanding the picture as a whole — important to understanding how truly depressing this situation is from all angles:

These aren’t inherently evil people doing evil things for the sake of evil. They’re just human beings trying to scrape a living out of extreme poverty. They’re hungry and live next to a massive wildlife area, full of game, full of food ripe for the taking.

That’s part of what makes this issue so wicked to grapple with. One of the major causes of poaching is poverty. And in a country that is as poverty stricken and resource poor as South Africa, treating the problem at its source is going to take more than 60 armed bodyguards. It’s going to take national reform and economic development in South Africa — which is a long way off.

And with Chinese demand for ivory as high as it’s ever been, there is enough fuel to keep this awful fire burning for a very long time. Perhaps until there’s no more ivory animals left to poach.

“I know it sounds depressing,” Mastrantonis says. “But I'm just kind of trying to be a bit more real about it. It's not as cut and dry as I think people think it is.”

Until a more comprehensive solution is found to stop poaching, game bodyguards like Stan Mastrantonis will have a job. They’ll be out there patrolling the savannah, deterring poachers, and holding their fingers in the dam of extinction, hopefully slowing the disappearance of endangered African elephants and rhinos.

Leave a Reply