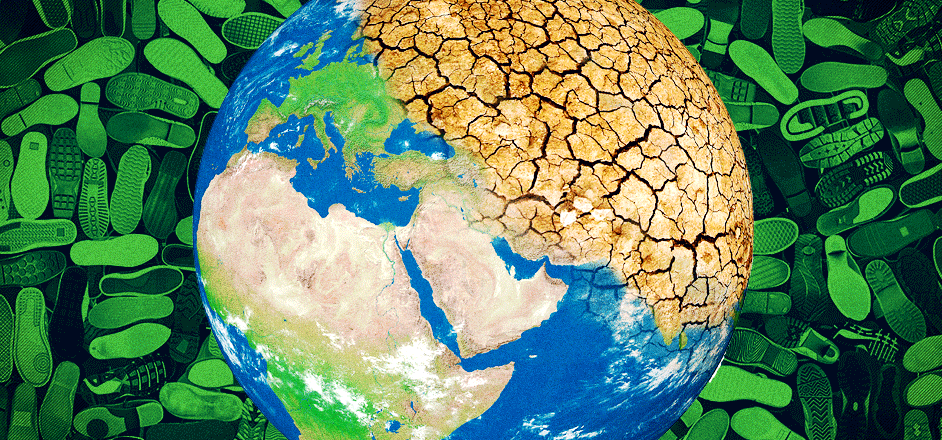

Your shoes are killing the planet. Yes, those ones down there on your feet. The “carbon footprint” they leave on our environment is far larger than the one they leave in the dirt — and that’s something that stands true even for the so-called “eco-sneakers.”

Maybe you thought you were making an environmentally conscious decision, spending an extra $50 on a pair of shoes that was made using recycled materials, made out of plastic bottles or grocery bags fished out of the ocean. Maybe you thought you were doing the Earth a solid.

In fact, you were just the victim of a clever and altogether misleading marketing ruse. You got played.

Because, as Danny McLaughlin found after a lengthy and in-depth investigation of these “eco-sneakers,” the amount of carbon saved in the production of these shoes is negligible compared to regular sneakers. To the point where you’re probably better off just buying shoes that will last longer.

“Over the last couple of years we’ve seen more ‘eco sneakers’ coming out, which is the ‘sustainable sneaker’ or ‘clean sneaker,’” says McLaughlin in his thick Scottish accent. McLaughlin is one of the co-founders of Run Repeat, the world’s number one running shoe review site, and a self-proclaimed sneaker-fanatic.

“I was kind of smelling a bit of bullshit so I thought, maybe I’d look into it some more and see how much better these eco-sneakers actually are for the planet and how much is just a marketing ploy.”

He began with a study, done by MIT: in it, researchers calculated the carbon footprint of a single pair of sneakers, from birth to death. They found that a typical pair of athletic shoes produces about 30 pounds of carbon dioxide gas over its lifetime — including production, shipping (from China), maintenance and care.

That was his baseline.

From there McLaughlin was able to calculate and compare the impact of an eco-sneaker to that of a regular sneaker. And he quickly began to realize that, the only real difference between eco-sneakers and regular shoes was the materials they used to make them, while the shipping, maintenance and cleaning costs all remained exactly the same.

“The biggest emissions come from the energy used in the factories in China, which is about 65 percent,” says McLaughlin. “So if they’re made in the factories in China, the most they could ever reduce the emissions by is 35 percent.”

Even then, when companies like Adidas, Brooks and Nike say they used plastic pulled from the ocean to create their shoe, they really mean, they used that plastic to create one part of their “eco-sneaker.” That could be the insole, outsole, midsole or upper part of the shoe, but almost never means the entire thing. So, you’re paying for an eco-aspect of a regular sneaker.

To put that into context, here are the numbers that McLaughlin extrapolated for two of the most popular eco-sneakers, from two popular brands: Brooks and Adidas.

- The Adidas Ultra Boost Parley (made using recycled bottles pulled from the ocean): 27.9 pounds of carbon emitted; .75 pounds of carbon reduced – in total, it’s a 9.6 percent reduction in carbon emissions.

- Brooks Adrenaline GTS 19 (with a biodegradable mid-sole): 30.1 pounds of carbon emitted, .75 pounds of carbon reduced from a regular shoe – in total, it’s a 2.5 percent reduction in carbon emissions.

“I believe that these companies are jumping on the eco bandwagon because they think it sells rather than because they’re doing what can actually make a difference.”

Now, the environmentally minded readers out there are probably thinking, “Well, even a 2.5 percent reduction in carbon emissions is something, and that’s worth paying for!”

But, not really, according to McLaughlin. Not only are these eco-sneakers, on average, almost 70 percent more expensive than their regular counter parts, but they don’t last as long. The quality of these eco-sneakers is consistently worse than the quality of a regular pair of shoes, and that means they wear out faster. Burn through two pairs of eco-sneakers in the time it would normally take you to burn through one normal pair and you’re actually increasing your carbon-impact on the planet by nearly a factor of two.

“You’re actually better buying a pair of shoes that aren’t eco-sneakers, that will last you a little bit longer rather than having to replace these flimsy things every two or three months and compounding the amount of emissions you’re using.”

McLaughlin also suggests that consumers try and limit their consumption of shoes as much as possible. Can’t decide between two pairs of kicks? Don’t buy them both, pick the pair that will last you longer. Like the same pair in blue, black and grey? Just pick the color you like best, don’t buy all three.

On the production side of things, it’s a little trickier. Since it’s the factories in China that produce the majority of carbon associated with a pair of shoes, companies like Adidas, Brooks and Nike would all have to enforce their own environmental regulations on their factories. Which they aren’t likely to do on their own.

“The problem is, that will cost [these companies] money,” McLaughlin points out. “How do you force a company to do what’s against their interest?”

Another option, McLaughlin suggests, would be to require companies to put carbon emission information about a product on its packaging — kind of like nutritional facts on the outside of food products.

“I’d be interested to see something like that on mass produced products,” he says. “And then at least consumers can make an informed decision.”

The only other option for making the business of making sneakers more sustainable would be a carbon tax. Essentially, charging companies like Nike and Adidas money for producing too much carbon. It’s the only realistic way of putting a financial incentive on sustainable practices of production, McLaughlin says.

While there are some eco-shoe companies out there that might be genuine (ie Toms), by in large, the big shoe producers who are putting eco-sneakers on the market, are capitalizing on their customers desire to reduce their carbon footprint. They know sustainability sells and they also know, their customers can’t tell the difference.

So long as they can slap the “Eco-“ label on a product, environmentally concerned consumers will throw cash at it. Regardless of how "Eco" it actually is.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.