Frontman Alex Ebert opens up with us about the festival culture and how artists should be valued by industry standards …

There’s a sharpened double-edged sword that lies in waiting in regard to public visibility. To build a personality — or in Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros’ frontman Alex Ebert’s case, a band — means to be relatable, and to use the comfort of familiarity to build a fanbase. Never change what people have come to love, however, because the confusion will turn them ungratefully sour in an instant.

Which is exactly what happened when the band asked co-vocalist Jade Castrinos to take some time off. The reasoning for last June’s split is still debated, as the band tries to keep its personal affairs personal, but fans still go ballistic on the act’s social media postings whenever something is said. The remaining ten continue on with divided supporters, though. The current lineup is working on a new album, in fact, with a release date still unknown.

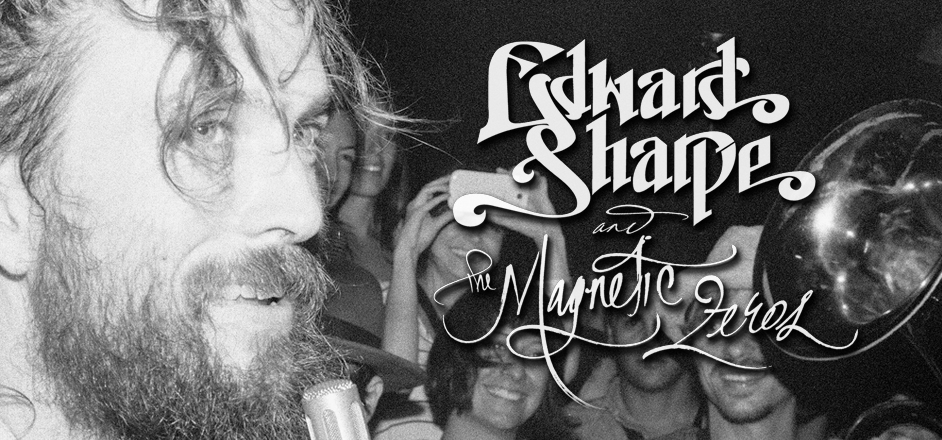

It’s during a studio session that we catch up with Ebert on the phone and speak with him about the changing face of music, what type of a musician he enjoys being and how he feels about the experiential festival style like that of the Arise Music Festival — one he and his band headline in Loveland, CO on Aug 7-9.

As a musician, what do you value more: being on stage in front of fans, or secluded writing and recording music?

On its face, in all aspects, I suppose the creation part of songwriting and recording is a very comfortable place to be. There’s no social anxiety involved; you’re just in communion with the spirit world and that’s it. As opposed to feeling you’re in the problematics that go into living on earth with a bunch of people.

And then, of course, there’s the whole thing of sleeping on a bus, which for a time can be fun, but it gets pretty exhausting. Especially when you work really, really hard, and you’re counting on good sleep.

You probably have to feed off the crowd’s energy then?

Yeah, you have this thing when you’re on stage, and you’re in communion with the people there; that’s pretty much one of the most unstoppable experiences that I’ve experienced. Playing live is a beautiful, beautiful, beautiful thing. It’s always undeniable. Every time it recharges you. When you’re on tour, that is your recharge: the energy that the people give you.

You’ve been doing this long enough to see this transitional period we’re in, where the Internet is beginning to run most of the show. Do you see it as a good thing or a bad thing?

You know, I think the jury’s still out. I think that communication-wise, tech progress has always been about shortening the duration of intention and realization. I think the Internet serves that purpose. But … god … ya, it at some point got to be a self-organizing, self-reducing platform. The only way it can become that and become artful and beautiful is each individual has to make it so.

At the moment I just don’t see that as being the case — the technology has made a musician out of everyone in the capitalist sense. Not the heartfelt sense, and the real sense, and the urgently artistic sense. And that’s shitty.

A main topic between artists and fans is the value of music. In your own words what is music worth to you?

Well, no, music should not be monetized … but neither should food. As soon as I can go into a market and shop for free, then you can have my music for free. While we’re in this capitalist society, it’s totally belligerent to be like: “Ya, music should be free and artists are my bitch that I steal from whenever I want to.” No that’s not right either.

Artists need to be respected in whatever economic paradigm we’re going to exist within. Without art, we don’t have culture, and without culture, we don’t really have much of humanity. I support artists sticking up for themselves with regard for getting paid — at the same time I’m looking towards a post-capitalist (society) eagerly.

The Arise Festival tends to be like that. It’s a very posi-vibe platform with things like yoga classes, meditation, arts, crafts … it’s more experiential than others. Do you see more festivals going this way, or will they stay as the profiteering monsters most of them are now?

I think if you just look at the history of things, you have those behemoths that are always sort of running concurrent alongside these independent operations, on any level of existence. I do think though that this is sort of a solid thing going on. There’s this slow roll of change towards a more communal, more experiential, more grounded movement. And that’s a positive thing.

(These festivals) are not in response to anything, is what I’m saying, like ‘Fuck the Vietnam war’ or anything like that. It’s almost entirely a positive experience, as opposed to reactionary. What you’ll have to look for is the big ones — this is what always happens — co-opting the idea of the experiential festival and the big giant juggernaut names putting on their own mega-version of it.

At the same time you have to wonder if that’s a bad thing. If good things go mainstream is it bad or good?

– Photos by: Nora Kirkpatrick and Stewart Cole

Leave a Reply